It All Belongs to Me

1927Sung by Ruth Etting

Ruth Etting (1934)

Pop music is rather different today than it was almost one hundred years ago. Though catchy melodies, songs about desire, and the conveying of emotion are a common thread, one big difference is in the role of the vocalist.

In contrast to pop songs today in which singers may have a say in their creation or even author their own lyrics, even using them as a vehicle for self-expression, commercially in-demand singers of the 1920s and 1930s sang song after song written by the industry’s dedicated composers and lyricists.

The song structures themselves were also different, and a key part of the songs that is often forgotten today can tell us so much more about the stories behind the melodies.

LYRICS

INTRO VERSE

Take a look at the flower in my buttonhole

Take a look say and ask me why it’s there

Can’t you see that I’m all dressed up to take a stroll?

Can’t you tell that there’s something in the air?

I’ve got a date, can hardly wait

I’d like to bet she won’t be late

CHORUS

Here she comes, come on and meet

A hundred pounds of what is mighty sweet

And it all belongs to me

Flashing eyes and how they roll

A disposition like a sugar bowl

And it all belongs to me

That pretty baby face

That bunch of style and grace

Should be in Tiff’ny’s window

In a platinum jewel case

Hey there you

You’ll get in dutch

I’ll let you look but then you mustn’t touch

For it all belongs to me [...]

Press play to listen along:

In this example, the narrator uses the personal pronouns “I” and “me” to situate the song from their point of view as the story proceeds. A non-gendered main character, the person describes the the attractive qualities of a woman they are about to go on a date with- and are rather possessive of! With Etting’s feminine voice taking on the role, the queerness of the song is made possible.

Consider the famous song ‘Ain’t She Sweet?’ from 1927, a song that has been recorded countless times in the decades since, and even by the Beatles. Though their 1960s version skips the intro verse, we can look to older recordings such as Lillie Delk Christian’s rendition to see the song structure most 1920s and early 1930s artists were singing.

Press play to listen along:

'Ain't She Sweet?' (1927)

Sheet Music,

Mississippi State

University Libraries

In the verse, the narrator’s use of ‘me’ pronouns identifies them as the character who is infatuated with a woman walking down the street; it is perhaps for this reason that the song was more commonly recorded by men. Another interesting oopsie gaysie example can be found on film, however.

When American actor Lillian Roth performed the hit in 1933 as a sing-a-long track, she used the verse as an opportunity to adjust the pronouns, keeping the more famous chorus untouched while changing the pronouns in the intro verse to “you.” Here, she literally “sets the story straight”, placing the role of the amorous gazer onto the audience. (Note the placement of the verse is later than usual in the song, starting at around 00:50)

Press play to watch, listen, and even sing along:

Lillian Roth in ‘Ain’t She Sweet?’ (1933)

Short Film

With this simple switch, she reveals the power of pronouns in changing the perspectives in the song, emphasising her role as a narrator and distancing herself from the lust expressed for the woman she is singing about.

By the time swing was the most popular style of jazz in the 1930s, large bands largely omitted the less danceable drifting intros and focused on rhythmic choruses. Even in the mid-1920s when introductory verses were still commonplace in ballads and recordings by smaller ensembles, many dance band orchestras playing foxtrot or Charleston numbers used them sparingly.

Let us consider the song “Charley My Boy.” Written in 1924, it was a popular song for dance band orchestras, which at the time mainly featured male vocalists. With the word ‘boy’ in the title, there is no ambiguity about the object of affection, who the narrator seems to be positively giddy for:

Bennie Kreuger and His Orchestra (date unknown)

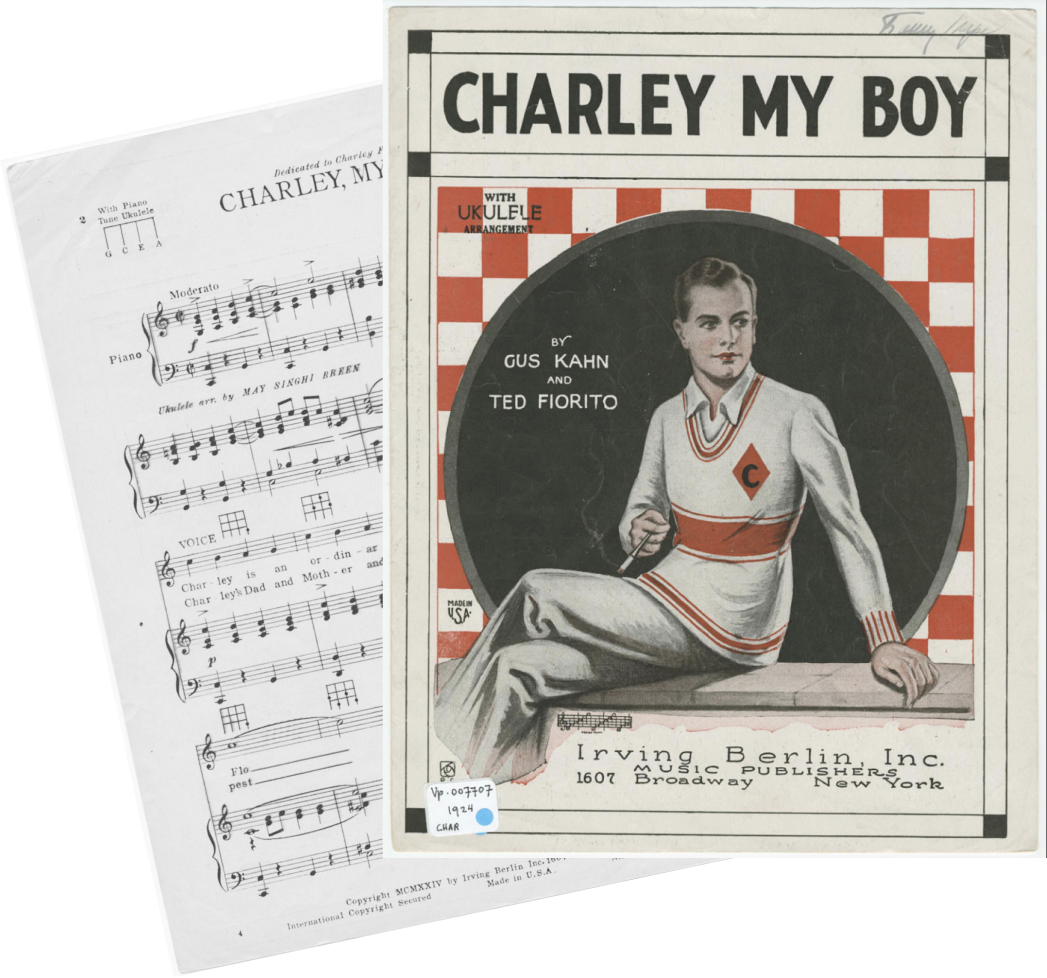

‘Charley My Boy’ (1924)

Sheet Music

Note the illustration depicting an artist’s version of the titular character. He is well-coiffed and youthful in appearance, dressed in fashionable US collegiate style clothing. Sensitive, well-groomed men were seen as very desirable during this decade.

Listen to the verseless Bennie Kreuger’s Orchestra version below sung by Billy Jones, a popular dance band vocalist in the mid 1920s:

Press play to listen along:

LYRICS

Charley my Boy,

Oh Charley my Boy

You thrill me, you kill me

With shivers of joy

You've got the kinda sorta

Bit of a way

That makes me takes me

Tell me what shall I say?

And when we dance

I read in your glance

Whole pages and ages

Of love and romance

They tell me Romeo was

Some lover too

But boy he should have

Taken lessons from you

You seem to start

Where others get through

Oh Charley my Boy.

Other versions of this common oopsie gaysie, however, leave the verse intact. These recordings reveal that the song, despite the use of the gender-neutral “I” pronouns in the chorus, was written from the perspective of Charley’s girlfriend.

In the version below, the exposition at the start of the song sets up the singer, Eddie Cantor, as playing the part of ‘Flo’. Just a few lines give context to the song that would otherwise not be clear, setting up the vocalist as relaying the story of a female character in a heterosexual relationship:

Press play to listen along:

Cantor’s sometimes subtly gendered vocal affectations as he relays Flo’s perspective are clues that he had a penchant for portraying over the top characterisations across race, gender, and ethnicity; like many popular singers of his day Cantor’s pre-radio and recording career started on the vaudeville circuit.

LYRICS

INTRO VERSE

Charley is an ordinary fellow to most everyone but Flo, his Flo

She’s convinced that Charley is a very extraordinary beau, some beau

And every evening in the dim light

She has a way of putting him right

CHORUS

Charley my Boy,

Oh Charley my Boy

You thrill me, you kill me

With shivers of joy [...]

There, he was best known for his comedy skits, portraying stereotypical depictions of Jewish people, spoofing his own heritage. Concurrently, he was an especially big name in the disturbingly enduring stage tradition of blackface. Although ‘Charley My Boy’ is not specifically racialised, having a third-person verse at the beginning of the song allows listener to understand the context of the singer’s act, and solidifies his role as a comedic storyteller- rather than a queer man in love.

Listen to more recordings with a significant intro verse that shares who is singing the song, or continue to the next exhibit to discover how the people being sung about significantly shaped the meaning of the music.