He's My Secret Passion

1930Danny Yates and His Orchestra

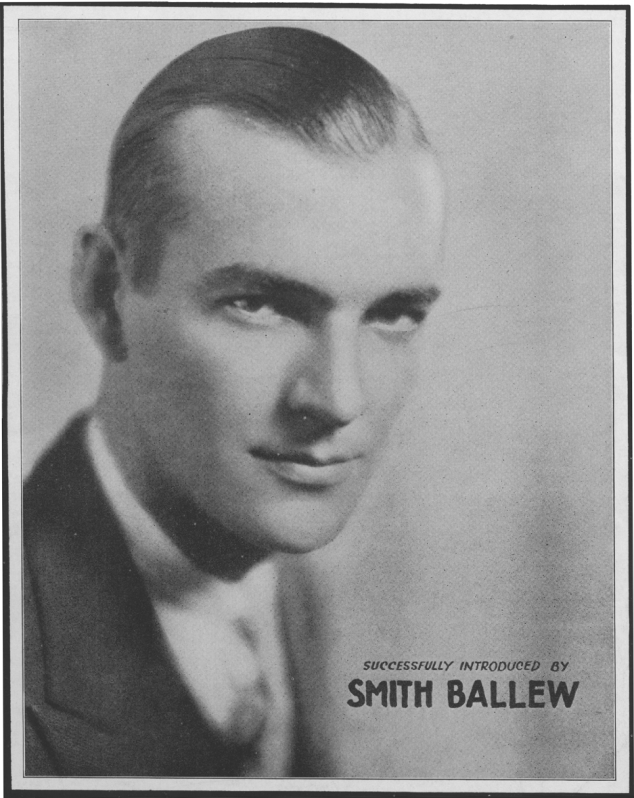

Sung by Smith Ballew

As the 1930s came to an end, so did the era of abundance for openly casually queer songs. Popular music styles were shifting away from vaudeville (and narrator and related character songs slowly with them) as other sounds, such as that of big band swing, reached new heights in popularity.

Though songs open to casual queer readings certainly exist in the 1940s and 1950s and beyond, they are much more unusual to find. Shifting from innocuous to suspicious, ‘sounding queer’ was taking hold on the public consciousness.

Smith Balley (c.1931)

Press play to listen along:

LYRICS

I'm at my window each morning at eight

My day begins when he passes the gate

He doesn't know it, but someday he will

He's my secret passion

I gaze for hours at the house where he lives

You can't imagine the thrill that it gives

I know I show it, but that's how I feel

He's my secret passion

I’m trying to find among my friends

One who knows him too

I'll be introduced to him by friends

If it's the last thing that I do

And at the café where he dines at nine

I sit and wish that the cooking were mine

He doesn't know it, but someday he will

He's my secret passion

“He’s My Secret passion” was originally featured in a British crime drama, and tells the story of a woman harbouring intense feeling for a man who is unaware of the narrator’s obsession. Smith Ballew’s vocals sing the melody in a sincere and intimate style indicative of crooners of the early 1930s. As he recites the lyrics about a secret love, it is easy to imagine that he is expressing he’s deepest feelings for another man.

Other male vocalists at the time did not sing the song this way, performing a version in which “he” was changed to “she”. Indeed, 1930 copies of the sheet music include a section plainly titled ‘She’s My Secret Passion (Male Version)’, revealing the publisher’s understanding that the lyrics were gendered. (Along with pronoun swaps, the alternate version interestingly changes the location in the last stanza from a café to a train.)

We may never know why Ballew (or the bandleader) chose the ostensibly “female version” to sing, but we do know that this would not have been seen as an unusual performance. Take the 1929 song “I Want To Be Bad”, which was also performed by a female character, in this case on both the stage and film. From the American romantic comedy Follow Thru, listen to a version by the eminent British dance band, Ambrose and His Orchestra:

LYRICS

If it's naughty to rouge your lips

Shake your shoulders and twist your hips

Let a lady confess, I want to be bad

If it's naughty to vamp the men

Sleep each morning till after ten,

Then the answer is yes, I want to be bad

This thing of being a good little goody is all very well

What can you do if you're loaded with plenty of health... and vigour?

When you're learning what lips are for

If it's naughty to ask for more

Let a lady confess, I want to be bad!

Here, a specifically transgender reading is made possible and probable as male crooner Lou Abelardo’s vocals portray the main character. Unlike many songs that use “I” pronouns in which the singer’s gender is left open, the lyrics reveal that the narrator is the proudly seductive lady in the song.

In 1929 when Abelardo was performing his casually queer chorus, expectations of masculinity and sexuality looked quite different than they do today. Indeed, as American studies scholar Allison McCracken has written about in depth, at the time, men were largely not marked as effeminate because of their soft high voices, groomed appearances, or the songs they sung. Generally, their performances did not incite widespread questioning of their assumed heterosexuality.

This would not last. As McCracken describes, by the early to mid 1930s, a shift was taking place; potential correlations between gender expression and sexual orientation were being increasingly made in the public sphere. Men perceived as feminine in any way, were at risk as being targeted as ‘pansies.’

Songs that hinted at any form of gender deviance would no longer so easily slip under the radar of the “immorality” censorship that was ramping up across media. From movies to nightclubs, real or imagined signs of queerness would be increasingly clamped down on across entertainment and society.

The skewed gender ratios in the second half of the 1930s is noticeable in The Record Collection, and a convergence of factors might best explain this discrepancy. The persistent popularity of songs about women, the rising prevalence of featured female vocalists in big bands, and gender differences in how queer sexuality was perceived and policed, were all at play.

Two of the most lyrically unusual oopsie gaysie songs from this era attest to the longevity of romantic longing for women as a theme in music. They were, however, re-imagined to fit into the sounds of the time. When Bea Wain recorded “Martha” in 1938 alongside the orchestra of Larry Clinton, who famously gave classical songs jazz arrangements, she was interpreting a song from an old German opera. When Maxine Sullivan sang “Annie Laurie” the year before, she was reciting a story that started as a 1700s Scottish poem. Their interesting histories are easy to hear:

Press play to hear “Martha”:

Press play to hear “Martha”:

Both are arrangements based on songs from the previous century, reinterpreted in the jazz-influenced styles of the day. Perhaps less threatening to heterosexual norms than men singing about their secret passions, love songs themed around women and featuring female vocalists, were still produced in moderation.

Opportunities for queer readings, however, never disappeared. Even throughout the era where vocalists unabashedly sung songs that sounded like homoromantic love stories, there are a multitude of ways to connect with the queerness of the past through music.

Perhaps you have heard of the song ‘Them There Eyes’. Written in 1930, it has been performed countless times since, with Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and Bing Crosby, all recording versions during the decade. Try listening to the version below by the American band Kansas City Six with vocals by guitarist Freddie Green, while paying attention to the use of pronouns:

LYRICS

I fell in love with you first time

I looked into them there eyes

You've got a certain way of flirtin'

With them there eyes

You make me feel so happy,

You make me feel so blue

I’m fallin’, No stallin’

Fallin’ in a great big way for you

My heart is thumpin’,

Solid jumpin’

Them there eyes

You'd better look out babe

If you're wise

Oh wise babe

They sparkle,

They bubble

They're gonna get you in a

Whole lot of trouble

Oh baby!

Them there eyes

Press play to listen:

Unlike many oopsie gaysie tunes, this one can be connected to queerness no matter who sings it. Throughout, the use of the non-gendered pronouns “I” and “you” allow anyone to relate to the perspectives in the song, while leaving the genders of the narrator and their love interest wide open.

Of particular interest to queer listeners is the inclusion of the word “they.” Though the lyrics imply the word refers to the lover’s eyes (which the potential interpretation of “them, their eyes” also supports), for non binary listeners it can be a way to hear themselves in the songs of the past loud and clear.

Though the amount of obvious oopsie gaysie songs declined along with shifts in the music industry, performance culture, and perceptions of gender and sexuality, they never disappeared. From same gender duets where only “I” and “you” is sung but the mood is certainly romantic, to songs themed around (what have become symbolic) rainbows, there are many ways to find queer possibilities in the songs of the past.

Listen to more recordings that are wide open for queer interpretations below, or visit the about page to read more about our vision, inspiration, research behind the project.