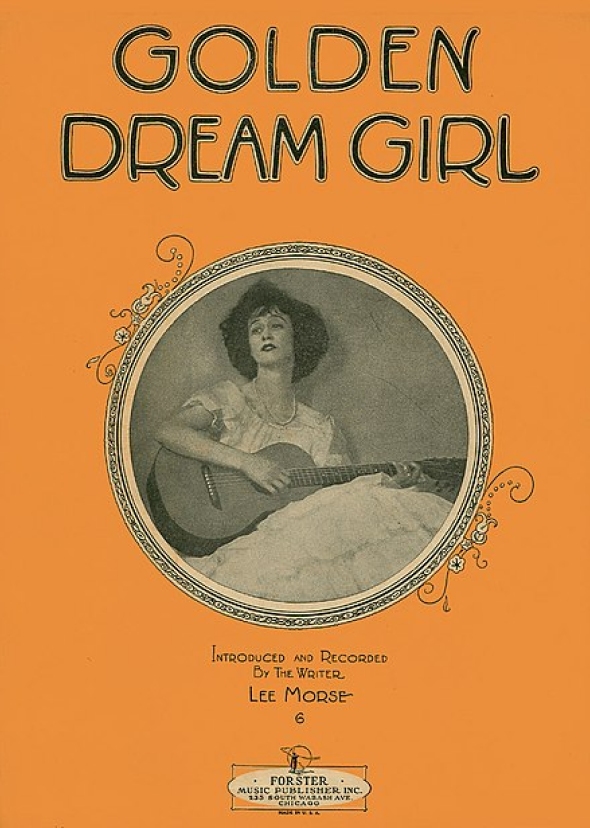

Golden Dream Girl

1924Sung by Miss Lee Morse

Lee Morse (c. 1930)

This practice of theming a song around a person is still common today, with popular songs across eras focusing especially on women as recipients of passionate emotions to tell stories (“Jolene”, “Billie Jean”, “Valerie”, and you can probably think of many more.)

Browse the Record Collection and you will notice that the writers of the 1920s and 1930s, the majority of who were men, produced these ‘name songs’ in abundance. When a female vocalist picked up one of these tunes about a woman, or a male vocalist about a man, a clear opportunity for queer readings is made possible.

Important to consider along with gender, many of the songs describing people often include markers of race, ethnicity, class, or place in their characterisations. From sincere sounding to clearly played for laughs, by looking at how the significant others are constructed in oospie gaysie songs, we can consider how the recordings are cultural artifacts. Each has the potential to reveal information about their creators, performers, audiences, and how they navigated categories of difference.

For writers creating love stories, songs about “faraway places” were a popular trend, with lyricists in the US and UK setting their tales of romance on distant shores. Lee Morse was a white American singer who reached the height of her fame in the 1920s. Celebrated for her deep voice and vocal stylings influenced by the blues, she stands out as a woman who played guitar and wrote many of her own songs, including “Golden Dream Girl” in 1924.

The crackly recording below documents a fascination that mainland Americans had with a simplified version of Hawaii, imagining the relatively newly taken territory as an idyllic paradise. The love interest in the story is nameless, portrayed an archetype waiting for the main character’s return on the “sweet Hawaiian shore”:

Lee Morse on the cover of

'Golden Dream Girl' (1925)

Sheet Music

Press play to listen along:

LYRICS

There's a song that haunts me

There's a girl that wants me

I'll always love her

Always think of her

But the fates win somehow

And I must forget now

"Farewell to thee"

That melody haunts me

Golden dream girl

You're my own South Sea pearl

Since that night on the sands

Your little brown hands

Set my world awhirl!

Oh, my South Sea flower

That enchanted hour

Makes my heart ache

To come back and take you home

For mine alone

Golden dream girl

I can see her standing

At the old boat landing

Brown eyes so tearful

Poor heart so fearful

Hopelessly believing

That her sweetheart’s leaving

Forever more

That sweet Hawaiian shore

Morse performed well oven a dozen oopsie gaysie songs during her career, serenading imaginary women from multiple US states and from around the world. Though we do not know why she was so fond of singing about women, in each case the settings they were placed in were key to the songs’ thematic packaging.

Take a song that is a lot more well known today and is the official song of the state it shares a name with. Though it has become associated with Georgian Ray Charles after his number one hit version in 1960, “Georgia On My Mind” was written in 1930 by two men from Indiana, Stuart Gorrell and famed composer Hoagy Carmichael.

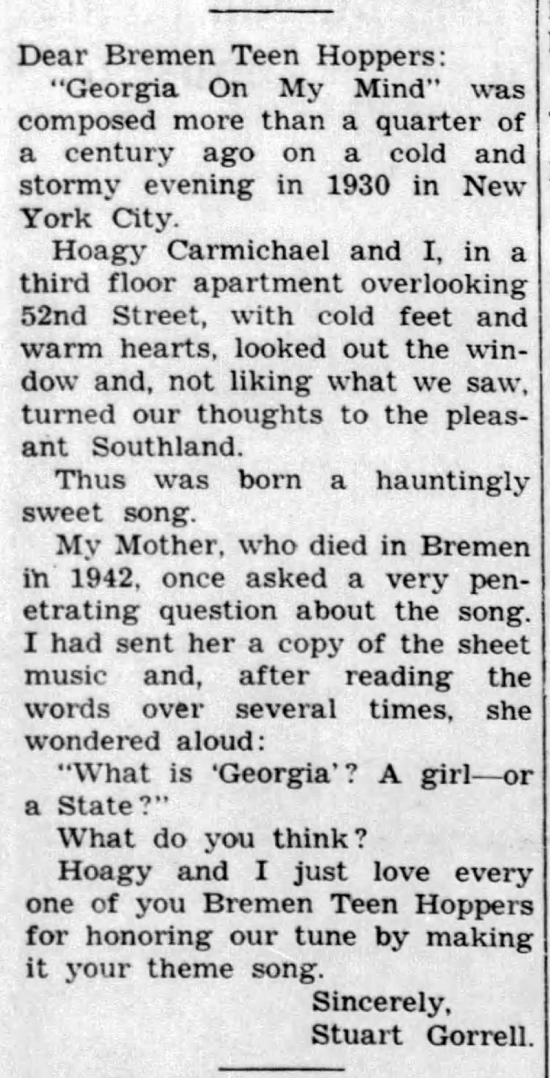

Letter from Stuart Gorrell

‘Bremen Enquirer’ Newspaper

(August 3, 1961)

With Georgia being both a woman’s name and the name of a geographic location, the song raises questions of who, or what, the lyrics are really about. It includes references to eyes and arms but also plants and roads, leaving the answer ambiguous.

The contradictory answers given by both songwriters add to the myth of the song. Lyrics writer Gorrell perhaps explains it best in a 1961 letter to a small newspaper near Atlanta, leaving the answer purposely open-ended: “What do you think?”

Listen along to the two versions of the potential oopsie gaysie below and see if you can answer his question.

Press play to listen along:

LYRICS

INTRO VERSE

Melodies bring memories

That linger in my heart

Make me think of Georgia

Why did we ever part?

Some sweet day when blossoms fall

And all the world's a song

I'll go back to Georgia

'Cause that's where I belong

CHORUS

Georgia, Georgia

The whole day through

Just an old sweet song keeps

Georgia on my mind,

Georgia on my mind

Georgia, Georgia

A song of you

Comes as sweet and clear

As moonlight through the pines

Other arms reach out to me

Other eyes smile tenderly

Still in peaceful dreams, I see

The road leads back to you

Georgia, Georgia

No peace I find

Just an old sweet song keeps

Georgia on my mind

Though neither of the two singers were from the state they were possibly singing about (Mildred grew up on the Coeur d'Alene Reservation in Idaho and Waters was from the Northeast, becoming part of the queer scene in Harlem) they would not have found it odd to sing a song about a Georgia. Rather, southern states were some of the most common topics in Tin Pan Alley music of the era, partly due to its association with jazz but also to the long tradition of depicting a nostalgic, idealised, and racialised version of the region.

From using symbols such as magnolia trees and the “old Bayou”, or assigning names to characters that at the time were linked to particular ethnic groups,there were many ways to conjure up images of both places and groups of people.

Both techniques were used in “Mah Lindy Lou” a 1920 song of romantic longing by white American Lily Strickland. The lyrics and title set the scene as somewhere in the South, a region where Strickland herself was from. The most unmistakable way Strickland wrote place and race into the piece, however, was by penning the lyrics in a dialect that was not her own. Rather, they were created in a crudely written approximation of Black Southern accents.

'Mah Lindy Lou' (1920)

Sheet Music

Lily Strickland

(date unknown)

When one of the first stars of radio, a white American woman known as Vaughn De Leath, recorded a version in 1929, she sang the words as written. As American studies scholar Allison McCracken describes in her book on crooning, a singing style that De Leath was instrumental in popularising, De Leath’s oopsie gaysie version can be understood as an ‘impersonation of a black man romancing a black woman’.

LYRICS

Honey, did you heah dat mockin’bird sing las’ night?

O Lawd, he wuz singin’ so sweet in de moonlight!

In de ole magnolia tree,

Bustin’ his heart wid melody!

I know, he was singing ob you,

Mah Lindy Lou, Lindy Lou!

O Lawd, I’d lay right back down and die,

Ef I could sing lak dat bird sings to you, Mah little Lindy Lou! [...]

Press play to listen along:

This troubling performance style may be shocking to hear on record now, though in some ways it is not surprising given the intertwined history of race and entertainment in the US. Many performers of radio and records got their start in vaudeville, where cross-race and cross-gender impersonations, including those influenced by racist minstrel shows, were a part of the performance culture.

Character singing gradually fell out of fashion over the years of the 1920s and 1930s, yet affected accents and ethnically coded words would remain in more subtle varieties. As artists picked up more personal sounding styles and songs, they also traversed the line between imitation and inspiration as diverse musical styles continually converged under the title of popular music.

The reverse-side recording of “Mah Lindy Lou” for instance, is another song about a woman written by Vaughn De Leath herself. “Marianna” is the more obviously humourous of the two sides. Though technically an oopsie gaysie, De Leath reciting lines about pasta and spaghetti in an over-exaggerated Italian accent reads less like a love song than a parody performance.

Even for singers that steered away from character songs, their vocal choices could shape the audiences’ perceptions of the relationships they were singing about. Although women rarely shifted their voices to sound particularly masculine as they serenaded women, and men also often sound quite sincere in their deliver of songs about men, listen closly to cross vocal performances and you can sometimes hear indications of gender awareness in their voices.

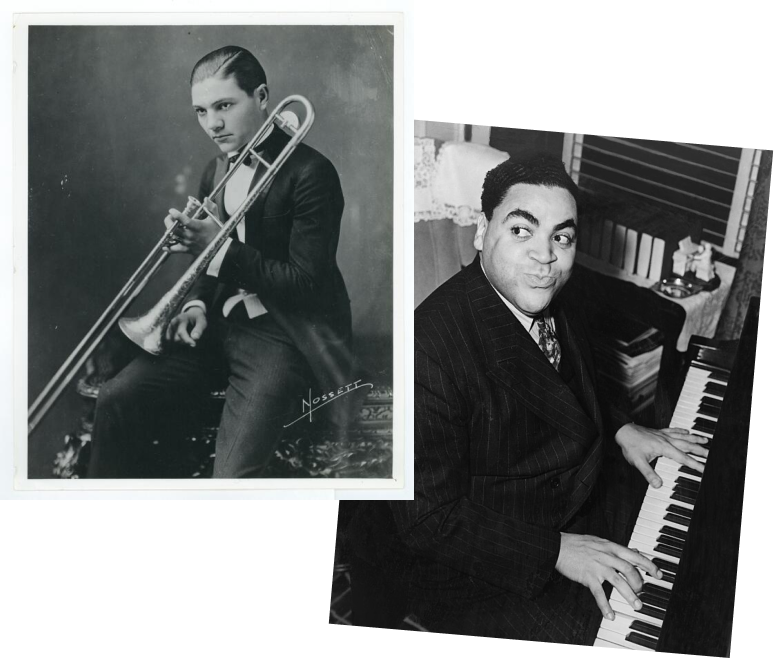

When two of the greats of jazz came together to play the lively song “That’s What I Like About You” in 1931, pianist Fats Waller and trombonist Jack Teagarden performed the song as a duet. Here, neither one plays a narrator, as both take on either side of a two person relationship. The result is one of the most flamboyant oopsie gaysie songs in the collection as they sing back and forth to each other.

Jack Teagarden (1920s)

Courtesy of the

New Orleans

Jazz Museum

Fats Waller (1938)

Press play to listen along:

LYRICS

You can’t cook!

(Who can’t cook?!)

You’re thick and fat!

(Don’t talk about my velocity now.)

You never got no dough.

(Ain’t supposed to have none!)

You drink too much gin.

(Always drink my gine.)

And you’re tired?

(Always tired.)

You don’t do anything I like!

(Well you know I like everything that you like.)

You do?

(Yes!)

Do you like the skies of blues?

(Honey, you knows I love the skies of blue. And another thing-

I love everything that you love.)

That’s what I like about you [...]

Here, the two men take on the roles of playfully disagreeing, presumably heterosexual lovers. Although it is never explictly stated that Waller is playing the part of a woman (the “you” that Teagarden sings to), gendered clues in the song, including Waller’s singing tone, suggest it is the case.

Though many other same-gender duos and vocal groups took on the role as the narrator through acting as one cohesive singing unit, the two men in this example played up the gendered aspects of the song. In portraying a stereotypical bickering straight couple so profusely, they simultaneously create possibilities for queer interpretations.

Listen to more recordings below to find more tunes in which people and place are enmeshed, or continue to the next exhibit to see why queer sounding songs became harder to find as the 1930s came to a close.